Osler, Medical History, and Medical Libraries

"It is hard for me to speak of the value of libraries in terms which would not seem exaggerated. Books have been my delight these thirty years, and from them I have received incalculable benefits."

"Every day do some reading or work apart from your profession. I fully realize, no one more so, how absorbing is the profession of medicine but . . . you will be a better man and not a worse practitioner for an avocation. I care not what it may be; gardening or farming, literature or history or bibliography, any of which will bring you into contact with books."

Osler grew up in a home well-supplied with books--his clergyman father had a collection of about 1500--but they were mostly theological works. "Willie" was well-acquainted with the Bible by the time he was fifteen, yet found the Sunday reading a great trial. It was his first two mentors, Reverend William Johnson and Dr. James Bovell, who taught him to love books. Both men were well-read in philosophy, natural history, theology, and medicine and they loved the English language. They allowed their protégé free use of their personal libraries, and introduced him to works such as Sir Thomas Browne's Religio Medici, which strongly influenced Osler's choice of profession and became a cherished guide. By their example, Osler learned that education was an enjoyable, satisfying process that continued long beyond one's school years, and that broad and constant learning was a fundamental part of a life in medicine. He also became fascinated with the history of medicine and with the works of medical pioneers. As he progressed in his career as a physician and teacher, he would find that historical study added perspective and depth to his work.

From his early professional years, Osler believed that good libraries--including current literature and historical works--were essential to modern medical schools and to medical associations. As his career developed and his income grew, he subscribed to scientific and medical journals, and purchased rare medical books when he could. He left McGill University his collection of journals when he moved to the United States. In Philadelphia, he joined the library committee of the College of Physicians (which already had an impressive collection) and helped expand its holdings. When he moved to Baltimore, he left nearly a thousand of his own volumes, mainly journals, to various Philadelphia libraries. At Johns Hopkins, he again took a keen interest in building the collections of the medical school library and that of the Maryland State Medical Society, among many others. In his teaching, he required students to use those libraries and taught them how to research topics through original sources.

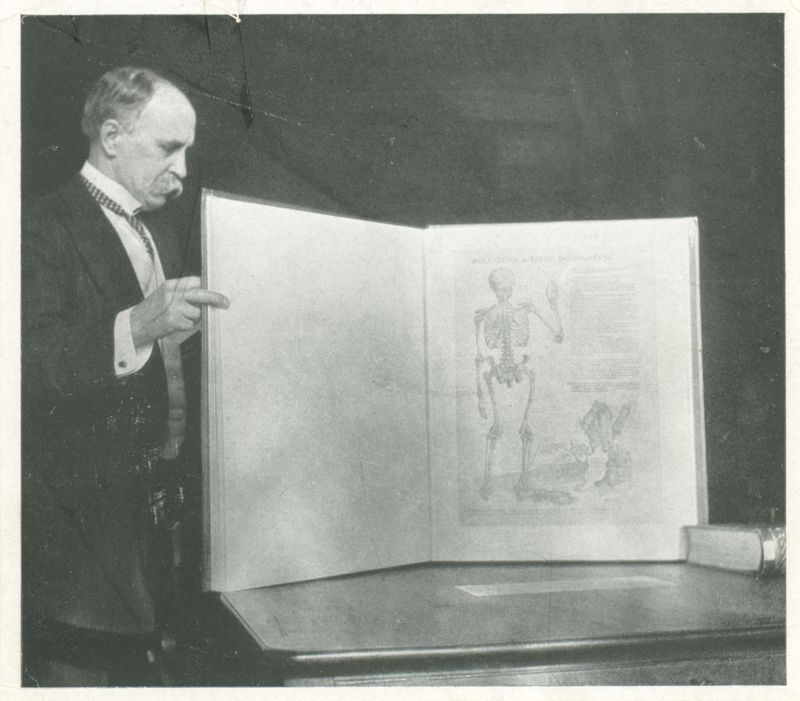

Wherever he went, Osler visited medical libraries. He talked to librarians, made suggestions for collection development, and often donated books that were needed. He urged his professional colleagues to take an interest, and contribute books and funds. His enthusiasm for medical history inspired others to collect incunabula and old classics, as well as secondary works on the history of medicine. If he found valuable old books in a library's collection, he urged the librarian to get them off the shelves, clean them, and display them.

Osler was very active with the Medical and Chirurgical Faculty of Maryland (later the Maryland State Medical Society) and provided the impetus to expand their collections, find better quarters for them, and raise money for a special historical collection. He also insisted that they hire a full-time professional librarian; he became a good friend and mentor to that first librarian, Marcia Noyes, who served the "Med-Chi" from 1896 to 1946. Osler and Miss Noyes, with several other physicians and librarians, founded the Association of Medical Librarians (now the Medical Library Association) in 1898, and Osler served as its president from 1901-1904.

Just as he kept in touch with old friends from all the phases of his life, Osler continued to look out for the interests of the libraries he had nurtured, even long after leaving one home for another. In his Oxford years, when he had more leisure and money for purchasing rare books, he continued to search out volumes he knew were lacking in one collection or another. Often he would donate these, or persuade one of his many philanthropist friends to buy them for the library in question.

Most of his own library, nearly eight thousand volumes, he left to McGill University, where it became the foundation of the Osler Library of the History of Medicine, opened in 1929. A self-described "bibliomaniac" to the end, Sir William Osler arranged to have his ashes, and those of Lady Osler, interred in a niche in the Osler Library, surrounded by those books he loved best, including his many editions of Sir Thomas Browne's Religio Medici.