Investigations of “The Narcotic Drug Problem” and further work on the Mental Examination of Aliens, 1923-1932

In the PHS assignment Kolb began at the Hygienic Laboratory in early 1923--investigating the extent and nature of narcotic drug use in the U.S.--he would establish himself as an expert on that topic. His work during this time would set the course of his subsequent career, and shape diagnostic classifications of addiction that became standard for the next 30 years.

Why did the PHS launch a five-year study of narcotic addiction at this time? The main target of "drug" reform campaigns during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries was alcohol, which was blamed for all manner of moral degradation, economic and family ruin, crime, and the deterioration of America's "racial stock." The long battle against alcohol culminated in 1919 with a constitutional amendment prohibiting the production and sale of intoxicating liquor (defined as having more than 0.5 percent alcohol content.) National alcohol prohibition became effective in 1920. However, the use of narcotics--a term that included heroin, morphine, and other opiates and to a lesser extent cocaine and cannabis--had also caused increasing concern since the late 1800s. In many states, such drugs were easily available in various forms, with few regulations. Some of the concern derived from progress in medical science and therapeutics, and growing recognition that many people became addicted to opiates via physicians' prescriptions for morphine and opium preparations like laudanum, "patent" medicine mixtures, and (sadly) commercial "cures" for alcoholism. At least half of these addicts were women, and most were white. Such "medical" use and addiction was starting to decline in the early 20th century, as the medical profession actively worked to discourage liberal use of narcotics in practice. In contrast, non-medical or recreational use had begun to increase and the user demographics were different: younger, more often male, more often lower class, and urban. Recreational drug use, like alcohol, became one of many social and public health concerns of the Progressive era, tied to worries about public order, changing social hierarchies, massive immigration, and shifting racial patterns. All these things, reformers feared, threatened to weaken American society along so many lines that its citizens would be easy prey for aggressive foreign powers, and America would cease to exist. As opiate addiction was more widely recognized as a liability by other countries, control of opiate traffic became a part of foreign policy as well. The 1912 Hague Opium Convention required signatories to commit to imposing controls on opium products. State and local public health officials also attempted to control narcotic distribution and addiction between 1900 and 1914.

The Harrison Narcotic Act of 1914 (which fulfilled America's Opium Convention commitment) was enacted to better regulate the sales of narcotic drugs, including morphine, heroin, and other opiates, as well as cocaine. (Cannabis wasn't included in the 1914 law, but the 1937 Marihuana Tax Act would impose similar restrictions.) It required anyone who imported, manufactured, produced, compounded, sold, dealt in, dispensed, or gave away narcotic drugs--physicians, pharmacists, dentists, veterinarians, importers, pharmaceutical manufacturers, and others--to register with the Bureau of Internal Revenue, obtain a tax stamp, and keep certain records. Initially, it wasn't intended to prohibit medical prescription or use of the drugs, only to ensure that unregistered users could not access them except through a prescription from a registered practitioner. Within a few years, though, legal challenges to early enforcement efforts gradually established that sound, "good faith" medical practice did not include prescribing drugs solely for the maintenance of addiction. By 1919, many physicians, fearing prosecution, had stopped prescribing narcotics for most patients, including those with legitimate medical needs.

This left many addicts in a desperate situation. For a short time, some cities attempted to set up narcotic clinics to supply addicts. Some of these provided maintenance doses, while others tried to gradually withdraw the addicts from the drugs by diminishing doses. By 1923, the Bureau of Internal Revenue agents (supported by the American Medical Association) had closed all of these facilities, and addicts who couldn't quit or find a sympathetic physician had to turn to black market supplies. There had been suggestions from the start of Harrison Act enforcement that the PHS take on responsibility for caring for addicts, but PHS leaders were not enthusiastic at first, and there were always too many competing budget priorities during the 1920s.

Kolb's first task was to establish the extent of addiction. This was difficult, because, especially after 1914, those who hadn't stopped using the controlled drugs, and hadn't been deemed "legitimate" addicts (e.g., those with incurable diseases or chronic pain) depended increasingly on illicit supplies. Morphine habits had always carried some stigma and were often hidden; the added prospect of criminal charges did not encourage addicts to talk about their condition. Physicians (some of whom were also addicts), also tended to be reticent about addicted patients. The first federal effort to estimate addict numbers, by a Treasury Department committee in 1918, used a wide range of state and local estimates along with surveys of physicians and pharmacists, but the committee admitted they couldn't vouch for the accuracy of the resulting report. Their report estimated that there might be as many as one million addicts. (Historian David Courtwright's excellent analysis of drug use between 1880 and 1920 concluded that there could not have been more than 313,000 addicts in America between 1900 and 1914.)

Kolb and Du Mez reviewed the earlier reports and conducted their own surveys. Their 1924 report concluded that most previous studies, including that of the Treasury Department committee, greatly overestimated the extent of addiction. The maximum number was closer to 150,000, and more likely lower, around 110,000 (of a population of about 114 million.) Moreover, addiction rates were clearly decreasing rather than increasing.

Kolb's second task was to find out more about addiction itself--how it occurred, the demographics of the addict population, whether there were different types of addicts, and what treatments helped them stop their drug use. Kolb located 230 known addicts with the assistance of revenue agents, local physicians, and superintendents of corrections facilities and hospitals. He interviewed them, collecting information on when and how their drug habits began, their preferred drugs and usual dose, and medical history. He also inquired about family history, education, occupation, police encounters, heredity, intelligence, temperament, and other aspects of their background. When possible, he interviewed family members and others in the addict's community. Based on this sample, Kolb identified five basic classes of addicts:

- 1) People of normal nervous constitution, accidentally or necessarily addicted through medication in the course of illness.

2) Carefree individuals, devoted to pleasure, seeking new excitements and sensations, and usually having some ill-defined instability of personality, that often expresses itself in mild infractions of social customs.

3) Cases with definite neuroses not falling into classes 2, 4, or 5.

4) Habitual criminals, always psychopathic.

5) Inebriates (those who compulsively binge on alcohol or other substances, rather than using them daily)

In his initial 1925 article on the five types of addicts, Kolb discussed them in detail, and summarized:

"Drug addicts in the United States are recruited almost exclusively from among persons who are neurotic or who have some form of twisted personality. Such persons are highly susceptible to addiction because narcotics supply them with a form of adjustment of their difficulties. A very large proportion of addicts are fundamentally inebriates, and the inebriate addict is impelled to take narcotics by a motive similar to that which prompts the periodic drinker to take alcohol. The so-called intoxication and narcotic impulses are identical. Some drunkards are improved socially by abandoning alcohol for an opiate, but the change is a mere substitution of a lesser for a greater evil."

The PHS addiction study also yielded eight other articles, which explored the relation of addiction to crime, the relation of intelligence to addiction, pleasure as a defining aspect of addiction, and the causes of relapse, among other topics.

Several other studies of addiction were done during the 1920s, including the Philadelphia General Hospital Drug Study (1925-1928), a controlled physiological investigation that established (among other things) that opiate addiction did not cause marked physical deterioration, and the New York Mayor's Commission on Drug Addiction study (1927-1929), which evaluated over 300 addicts and concluded, like Kolb, that psychological abnormalities were present in 87 percent of them. None of their authors, however, achieved the wide influence that Kolb did. In the decades between 1925 and 1965, as David Courtwright has noted, Kolb was the single most important and most frequently cited source for the psychopathic view of addiction.

As historian Caroline Acker has discussed, Kolb's addiction model embodied the contemporary psychiatric thinking that defined mental illness in terms of adjustment to social norms and roles. Kolb and others, including his staff at the Lexington Narcotic Farm, would modify this framework as time went on, but the main idea –that addicts became addicts due to fundamental psychological deficits--guided clinical, policy, and law enforcement thinking for the next forty years. Kolb was a kind and humane physician, and regarded "deviant personality" a better label than "criminal," but as Acker argues, this labeling placed addicts--and many others with mental illness--in diagnostic boxes that precluded any other interpretation of their condition. Almost inevitably, such definitions enabled punitive policy responses, though that was never Kolb's intention. As Courtwright observed, from the 1930s through the 1950s, Kolb was "instrumental in keeping alive in the United States the flickering belief that addiction was fundamentally a medical problem."

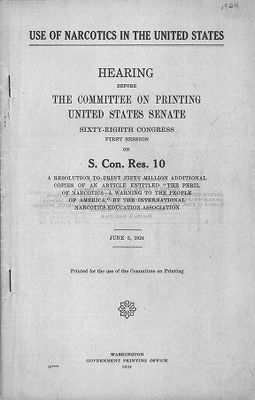

Kolb's research won praise from psychiatrists and the public health community, but anti-narcotic crusaders were less pleased with his conclusions, which refuted a number of their claims – that addiction was sweeping the nation and enslaving millions, that narcotics turned users into violent criminals, that drug dealers were preying on school children, and so on. One prominent crusader, Richmond P. Hobson, became an ongoing challenge for Kolb starting in 1924. A Spanish American war hero and former congressman from Alabama, Hobson had campaigned for alcohol prohibition for over a decade. After the Prohibition Amendment was enacted in 1919, he turned his energies to the "narcotic menace," which he attacked mainly via his organization, the International Narcotic Education Association (INEA). His primary message was that despite the efforts of narcotic law enforcers, there were millions of addicts, and their numbers were growing. Therefore, Hobson argued, it was imperative to educate Americans about the dangers of narcotics, and he saw his INEA as a leading agency in this effort. The organization published a journal for several years, and organized a World Conference on Narcotic Education in 1926. Hobson also used his contacts in Congress and in state legislatures to propose bills that would support his cause. In 1924, the Senate Committee on Printing held a hearing to consider Hobson's request to have the federal government print and distribute fifty million copies of his article "The Peril of Narcotics." Kolb, testifying at the hearing, told the committee that Hobson's document was full of errors and faulty analysis, that recent research didn't support the claim of millions of addicts, and that a propaganda campaign such as Hobson's would do more harm than good, creating a climate of fear. Kolb had met with Hobson the month before and discussed the addiction problem, so Hobson knew how Kolb was likely to testify. He tried to discredit him in the hearing, and continued to accuse Kolb and the Public Health Service of incompetence and sympathizing with addicts and drug dealers.

In response to these attacks, Kolb subsequently investigated and debunked many of Hobson's claims, contacting medical and law enforcement colleagues for their perspectives and additional data. He also investigated the INEA, its personnel and financial operations. Hobson, meanwhile, continued his crusade into the 1930s, including persuading Senator Royal Copeland to introduce a bill to establish a national college of narcotic education in 1927.

Kolb's addiction expertise would oblige him to counter anti-narcotic misinformation for the rest of his career. Kolb believed the Harrison Act was needed and that it prevented much of the medical addiction that was so common in previous decades, and encouraged addicts to stop using if they could. He didn't believe in maintenance of habits that were not connected to medical needs such as chronic pain (though later he changed his mind about this); but he always regarded drug users as victims of a psychiatric medical problem, needing treatment, not harsh punishment, and vigorously criticized characterizations of them as monsters, and addiction in general as some sort of plague. He frequently noted that alcohol was far more likely than opiates to induce violent behavior, and to cause physical deterioration. This often put him at odds with proponents of punishment, particularly Harry J. Anslinger, commissioner of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics, the Treasury Department agency that handled drug law enforcement from 1930.

Mental examination of prospective immigrants in Europe, 1928-1931

The Immigration Act of 1924 set quotas for the yearly number of immigrants permitted from each nation and charged consular officers in foreign countries with issuing immigration visas for those destined for the U. S. Per the new law, such visas were not to be issued if officers believed the applicants wouldn't be admitted under U. S. immigration laws. So, in addition to inspecting ships departing for America, PHS officers had to do medical and mental exams in many European port cities. Immigrants would still be examined at U. S. ports, but this measure was intended to reduce the number that had to be detained and deported at the U.S. side. In 1928, the Surgeon General assigned Kolb to a three-year overseas post, where he was to evaluate the mental testing of prospective immigrants being done at the European consulates, and work with medical officers to develop more accurate testing methods. Kolb later recalled that this assignment was prompted in part by a complaint lodged in 1927 by the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society that recent prospective Jewish immigrants at the Warsaw consulate were rejected for intellectual disabilities at far higher rates than those examined at U. S. ports in the preceding five years. When he arrived in Europe in 1928, Kolb and several PHS colleagues investigated, reexamined some of the cases in question, and found that many were not, in fact, intellectually disabled.

Kolb's work during this time included determining the types of tests that best reflected the abilities of different immigrant groups--Italians, Scandinavians, Germans, Irish, English, and others. He and his associates drafted a series of four articles reporting studies of these groups, but they were apparently never published. Kolb returned to the U.S. in 1931 and spent a year finishing work on the mental testing articles.