Sabin's Third Career: Public Health in Colorado, 1939-1951

Sabin's first years of "retirement" were comparatively quiet: She finished writing up her Rockefeller research findings, traveled with her sister, corresponded with friends and colleagues, attended professional meetings, and was an active advisory board member for the Guggenheim Memorial Foundation and the Henry Strong Denison Foundation, among others. She also served on the Board of Directors of the Denver Children's Hospital.

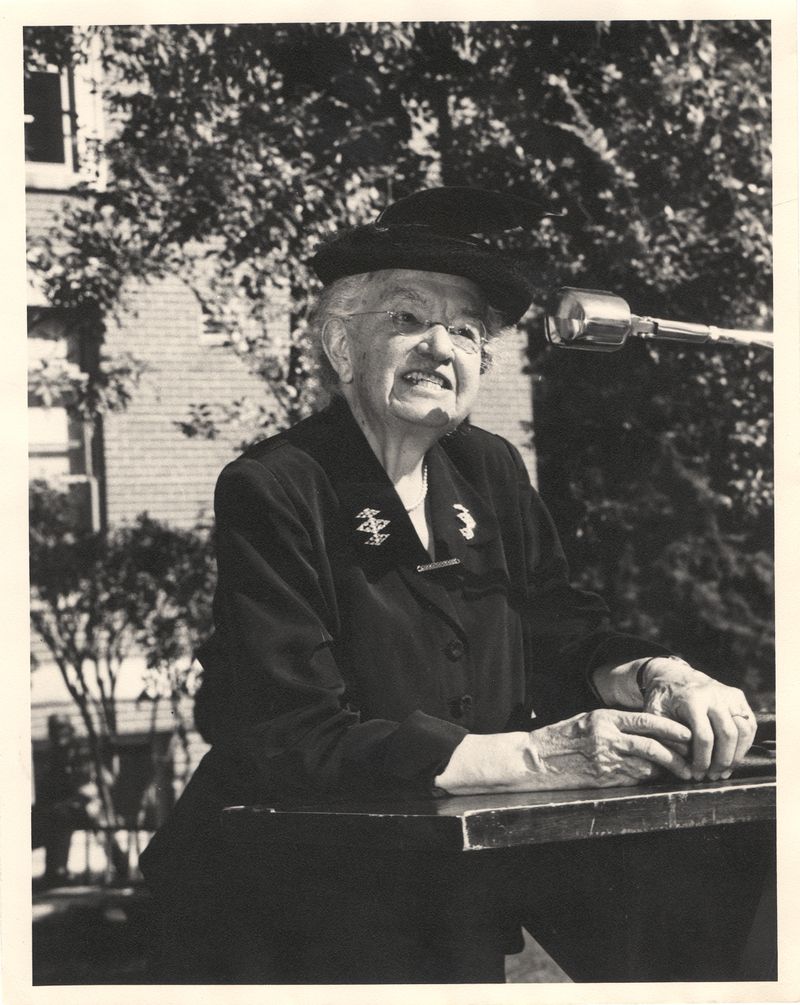

In December of 1944, Colorado governor John Vivian was organizing a post-war planning committee to prepare for the expected demobilization of U.S. troops the following year. A reporter for the Denver Post suggested that Vivian would do well to appoint a woman to his committee on health, and recommended Florence Sabin. Assured by several other people that Dr. Sabin was a nice (if brilliant) little old lady who would not rock the political boat, Vivian asked her to head the Committee on Health, and she accepted.

Fortunately for Colorado residents, the "little old lady" approached this responsibility with all the intelligence and energy that had characterized her research career. Sabin, though a researcher, was no stranger to the world of public health. Many of her longtime Baltimore friends, several of them physicians, had spent their careers practicing social medicine. Early in her career, Sabin had volunteered at the Evening Dispensary for Working Women and Girls in Baltimore, run by Drs. Lilian Welsh and Mary Sherwood. And her many years with the National Tuberculosis Association kept her in regular contact with the public health branch of that organization, and gave her a wide range of contacts to draw upon.

For the next two years, Sabin consulted many public health experts and arranged health surveys of all Colorado counties. These showed Colorado's morbidity and mortality rates to be unacceptably high, and its public health infrastructure to be antiquated and unacceptably poor. The Sabin Committee drafted public health bills to remedy the situation, and Sabin herself traveled around the state drumming up public support for new health legislation. She also effectively lobbied state legislators for their support. In 1947 the state legislature passed four of the six "Sabin Bills":

--A complete reorganization of the State Board of Health, which would change it from a division under the governor's control (and thus fair game for political patronage appointments) to a Department with a Board of Health providing advisory, consultative, and judiciary functions, and an executive division consisting of the state health officer and his staff. The Board would consist of nine members appointed by the governor in such a way that no business or professional group would constitute a majority.

--Provisions for adjoining counties with limited resources to organize district health services with federal, state, or local funds.

--An increase in the per diem allowance available to indigent hospitalized tuberculosis patients.

--Provisions to enable the state Department of Public Health to meet federal requirements for receiving funding for hospital construction under the Hill- Burton Act

The bills to set up a state tuberculosis hospital and to establish a strict program to control brucellosis, a serious cattle disease, were not passed.

Because the city of Denver accounted for one-third of Colorado's population (and a similar proportion of its health problems), Sabin believed that cleaning up the city should be a top priority. In December of 1947, she was appointed Manager of the city's Department of Health and Charities, and proceeded to campaign against sub- standard restaurant and hospital sanitation, contaminated milk, and rat infestation. She also campaigned for more preventive health care (including a mass x-ray survey in 1948 to identify cases of tuberculosis and other lung diseases) and enforcement of communicable disease laws. She continued to play an active role in the Denver Health Department, as Board member and chair, until 1951.

Sabin's last few years were spent largely in taking care of her sister Mary, whose health was deteriorating. The strain of this eventually affected Sabin's own health: after a bout with pneumonia, for which she was hospitalized, she returned home and died there several months later on October 3, 1953.